W3cubDocs

/TensorFlow GuideTensorBoard: Embedding Visualization

Embeddings are ubiquitous in machine learning, appearing in recommender systems, NLP, and many other applications. Indeed, in the context of TensorFlow, it's natural to view tensors (or slices of tensors) as points in space, so almost any TensorFlow system will naturally give rise to various embeddings.

To learn more about embeddings and how to train them, see the Vector Representations of Words tutorial. If you are interested in embeddings of images, check out this article for interesting visualizations of MNIST images. On the other hand, if you are interested in word embeddings, this article gives a good introduction.

TensorBoard has a built-in visualizer, called the Embedding Projector, for interactive visualization and analysis of high-dimensional data like embeddings. It is meant to be useful for developers and researchers alike. It reads from the checkpoint files where you save your tensorflow variables. Although it's most useful for embeddings, it will load any 2D tensor, potentially including your training weights.

By default, the Embedding Projector performs 3-dimensional principal component analysis, meaning it takes your high-dimensional data and tries to find a structure-preserving projection onto three dimensional space. Basically, it does this by rotating your data so that the first three dimensions reveal as much of the variance in the data as possible. There's a nice visual explanation here. Another extremely useful projection you can use is t-SNE. We talk about more t-SNE later in the tutorial.

If you are working with an embedding, you'll probably want to attach labels/images to the data points to tell the visualizer what label/image each data point corresponds to. You can do this by generating a metadata file, and attaching it to the tensor using our Python API, or uploading it to an already-running TensorBoard.

Setup

For in depth information on how to run TensorBoard and make sure you are logging all the necessary information, see TensorBoard: Visualizing Learning.

To visualize your embeddings, there are 3 things you need to do:

1) Setup a 2D tensor variable(s) that holds your embedding(s).

embedding_var = tf.Variable(....)

2) Periodically save your embeddings in a LOG_DIR.

saver = tf.train.Saver() saver.save(session, os.path.join(LOG_DIR, "model.ckpt"), step)

The following step is not required, however if you have any metadata (labels, images) associated with your embedding, you need to link them to the tensor so TensorBoard knows about it.

3) Associate metadata with your embedding.

from tensorflow.contrib.tensorboard.plugins import projector # Use the same LOG_DIR where you stored your checkpoint. summary_writer = tf.train.SummaryWriter(LOG_DIR) # Format: tensorflow/contrib/tensorboard/plugins/projector/projector_config.proto config = projector.ProjectorConfig() # You can add multiple embeddings. Here we add only one. embedding = config.embeddings.add() embedding.tensor_name = embedding_var.name # Link this tensor to its metadata file (e.g. labels). embedding.metadata_path = os.path.join(LOG_DIR, 'metadata.tsv') # Saves a configuration file that TensorBoard will read during startup. projector.visualize_embeddings(summary_writer, config)

After running your model and training your embeddings, run TensorBoard and point it to the LOG_DIR of the job.

tensorboard --logdir=LOG_DIR

Then click on the Embeddings tab on the top pane and select the appropriate run (if there are more than one run).

Metadata (optional)

Usually embeddings have metadata associated with it (e.g. labels, images). The metadata should be stored in a separate file outside of the model checkpoint since the metadata is not a trainable parameter of the model. The format should be a TSV file with the first line containing column headers and subsequent lines contain the metadata values. Here's an example:

Name\tType\n Caterpie\tBug\n Charmeleon\tFire\n …

There is no explicit key shared with the main data file; instead, the order in the metadata file is assumed to match the order in the embedding tensor. In other words, the first line is the header information and the (i+1)-th line in the metadata file corresponds to the i-th row of the embedding tensor stored in the checkpoint.

Images

If you have images associated with your embeddings, you will need to produce a single image consisting of small thumbnails of each data point. This is known as the sprite image. The sprite should have the same number of rows and columns with thumbnails stored in row-first order: the first data point placed in the top left and the last data point in the bottom right:

| 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | 7 |

Note in the example above that the last row doesn't have to be filled. For a concrete example of a sprite, see this sprite image of 10,000 MNIST digits (100x100).

After constructing the sprite, you need to tell the Embedding Projector where to find it:

embedding.sprite.image_path = PATH_TO_SPRITE_IMAGE # Specify the width and height of a single thumbnail. embedding.sprite.single_image_dim.extend([w, h])

Interaction

The Embedding Projector has three panels:

- Data panel on the top left, where you can choose the run, the embedding tensor and data columns to color and label points by.

- Projections panel on the bottom left, where you choose the type of projection (e.g. PCA, t-SNE).

- Inspector panel on the right side, where you can search for particular points and see a list of nearest neighbors.

Projections

The Embedding Projector has three methods of reducing the dimensionality of a data set: two linear and one nonlinear. Each method can be used to create either a two- or three-dimensional view.

Principal Component Analysis A straightforward technique for reducing dimensions is Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The Embedding Projector computes the top 10 principal components. The menu lets you project those components onto any combination of two or three. PCA is a linear projection, often effective at examining global geometry.

t-SNE A popular non-linear dimensionality reduction technique is t-SNE. The Embedding Projector offers both two- and three-dimensional t-SNE views. Layout is performed client-side animating every step of the algorithm. Because t-SNE often preserves some local structure, it is useful for exploring local neighborhoods and finding clusters. Although extremely useful for visualizing high-dimensional data, t-SNE plots can sometimes be mysterious or misleading. See this great article for how to use t-SNE effectively.

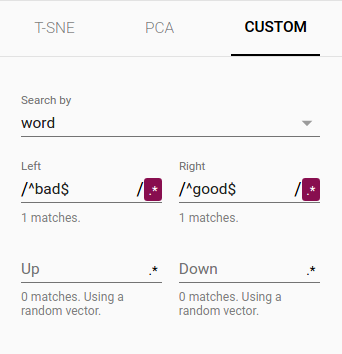

Custom You can also construct specialized linear projections based on text searches for finding meaningful directions in space. To define a projection axis, enter two search strings or regular expressions. The program computes the centroids of the sets of points whose labels match these searches, and uses the difference vector between centroids as a projection axis.

Navigation

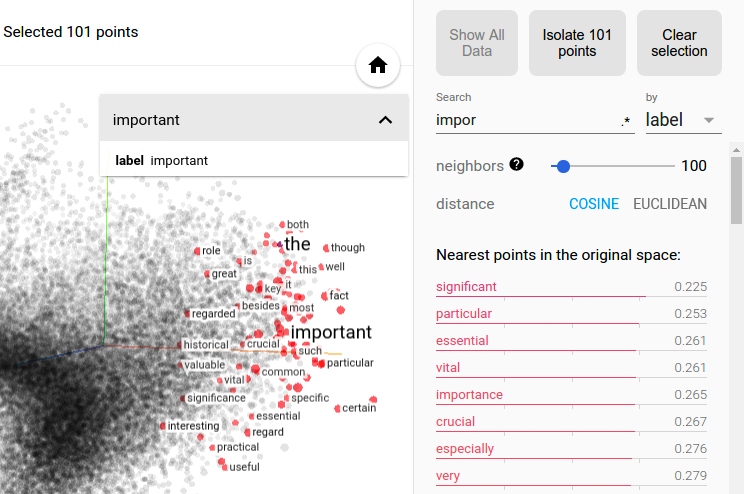

To explore a data set, you can navigate the views in either a 2D or a 3D mode, zooming, rotating, and panning using natural click-and-drag gestures. Clicking on a point causes the right pane to show an explicit textual list of nearest neighbors, along with distances to the current point. The nearest-neighbor points themselves are highlighted on the projection.

Zooming into the cluster gives some information, but it is sometimes more helpful to restrict the view to a subset of points and perform projections only on those points. To do so, you can select points in multiple ways:

- After clicking on a point, its nearest neighbors are also selected.

- After a search, the points matching the query are selected.

- Enabling selection, clicking on a point and dragging defines a selection sphere.

After selecting a set of points, you can isolate those points for further analysis on their own with the "Isolate Points" button in the Inspector pane on the right hand side.

Selection of the nearest neighbors of “important” in a word embedding dataset.

Selection of the nearest neighbors of “important” in a word embedding dataset.

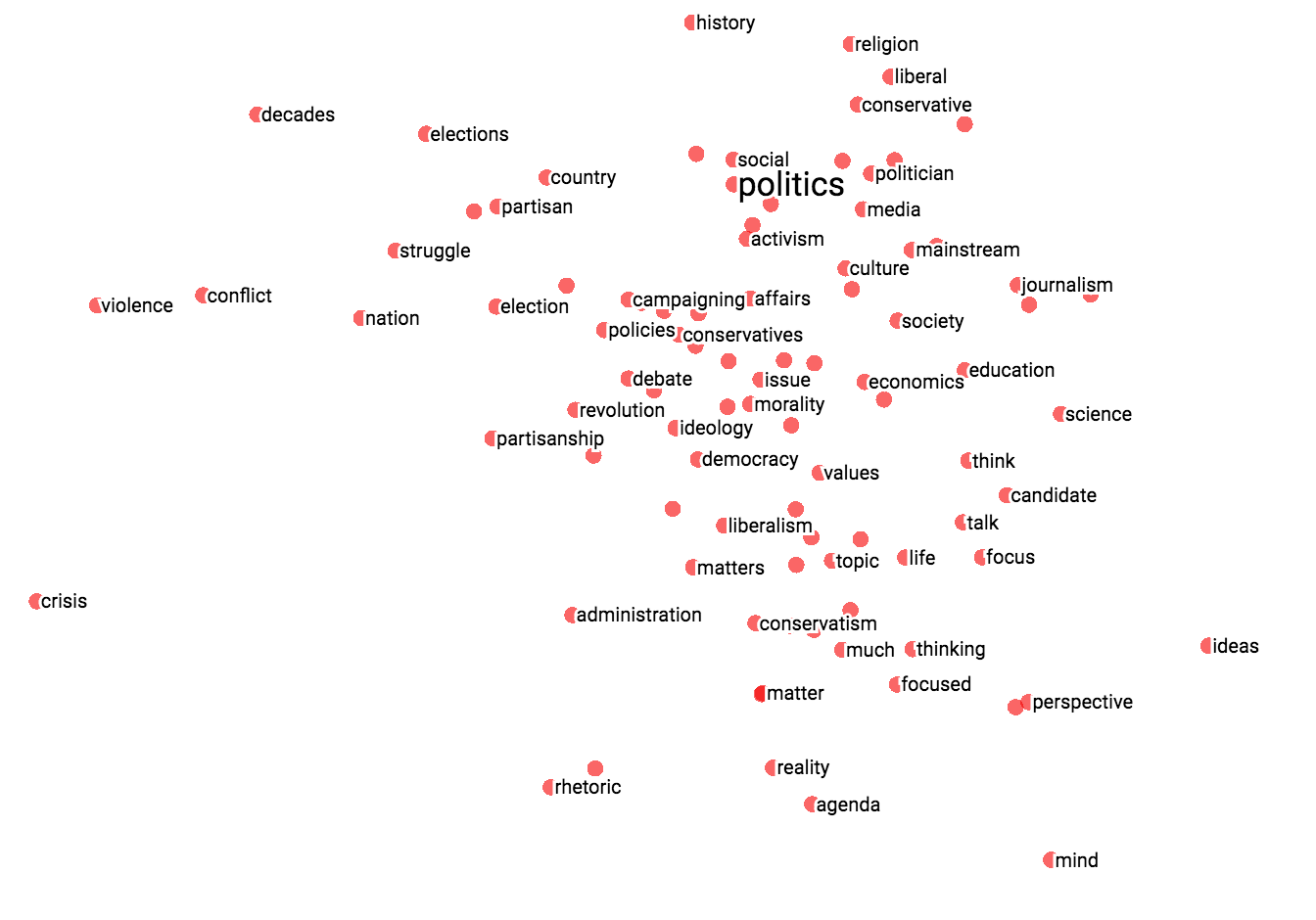

The combination of filtering with custom projection can be powerful. Below, we filtered the 100 nearest neighbors of “politics” and projected them onto the “best” - “worst” vector as an x axis. The y axis is random.

You can see that on the right side we have “ideas”, “science”, “perspective”, “journalism” while on the left we have “crisis”, “violence” and “conflict”.

|  |

| Custom projection controls. | Custom projection of neighbors of "politics" onto "best" - "worst" vector. |

Collaborative Features

To share your findings, you can use the bookmark panel in the bottom right corner and save the current state (including computed coordinates of any projection) as a small file. The Projector can then be pointed to a set of one or more of these files, producing the panel below. Other users can then walk through a sequence of bookmarks.

© 2017 The TensorFlow Authors. All rights reserved.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0.

Code samples licensed under the Apache 2.0 License.

https://www.tensorflow.org/get_started/embedding_viz